Reviews and articles

Reviews for OUR FEELINGS TOOK THE PICTURES: OPEN SHUTTERS IRAQ

Audience comments for OUR FEELINGS TOOK THE PICTURES: OPEN SHUTTERS IRAQ

Reviews for RETURN TO THE LAND OF WONDERS

Audience comments for RETURN TO THE LAND OF WONDERS

Reviews for OUR RIVER OUR SKY

Interview: ‘The shooting stops but the war’s not over’: making movies in post-9/11 Iraq

by Saeed Kamali Dehghan, 24 October 2023

Maysoon Pachachi’s debut fiction film explores the lives of intertwined characters living in Baghdad during the US occupation in 2006. Read

See awards the film has won.

Reviews for OUR FEELINGS TOOK THE PICTURES: OPEN SHUTTERS IRAQ

Iraqi women frame the human reality of conflict

'Open Shutters Iraq' turns pain and loss into a creative project

By Olivia Snaije

Special to The Daily Star

Tuesday, April 14, 2009

LONDON: Every once in a while a project so successfully portrays the universality of human emotion that it is both admirable and timeless. "Open Shutters Iraq" is one such project.

"Open Shutters" began as a series of photographic essays and has since become a documentary film of the same name. Both have grown from a photography workshop for Iraqi women initiated by British photojournalist Eugenie Dolberg, in Damascus in 2006, during one of the most violent periods of the recent Iraqi conflict.

Frustrated by the paucity of news coverage coming from Iraq, Dolberg wanted to find a way for Iraqi women to document the war with more intimacy. She and Irada Zaydan, a professor at the University of Baghdad, chose 12 women from five different Iraqi cities, all of different social, political and religious backgrounds, to participate in the Damascus workshop.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and the British organization Index on Censorship funded it.

Before the workshop opened, Dolberg asked London-based Iraqi filmmaker Maysoon Pachachi to document the process from beginning to end.

Dolberg and Pachachi and the Iraqi women lived together in a large house in Damascus' old city for the first segment of the workshop. The 12 participants then went back to Iraq to shoot their stories, returning to Syria to edit their work.

Pachachi filmed the women almost 24-hours a day for about two months. She couldn't finish editing the film until late last fall - as she was also in the midst of setting up a film-training center in Baghdad.

The film "Open Shutters Iraq" premiered at the Dubai International Film Festival last December and is presently in the documentary competition at the Gulf Film Festival, which ends on April 15.

"I think this film can have a resonance anywhere" says Pachachi, "because in essence it is about how the base material of trauma and pain and loss can be acknowledged and owned and then turned into a creative work which stands as an affirmation of existence in the face of the destruction and fragmenting of the world."

Pachachi's film introduces the women, among whom Raya, Lujane, Um Mohammed and Antoinette, the project manager, Zaydan and her six-year-old daughter Dima, Dolberg and her translator, as they begin a basic photography class.

Dolberg teaches the women about light and darkness, how to hold a camera and position themselves, how to re-train their eyes "to perceive the world in a completely new way." Once Dolberg has given the women some basic technical skills, she moves on to what she calls her "Life Map." This is when things start to get exciting.

Using writing and photographs glued to a sheet of poster-format-sized paper to pinpoint major events in her life, Dolberg recounts memories, experiences and sentiments about her identity. By revealing her vulnerabilities to the women, a mutual exchange is set in motion. It is now up to these women to work on Life Maps of their own.

Their subsequent presentations provide an astonishingly candid, generous, and often heart-wrenching overview of life in Iraq with one common denominator: War.

The loss and trauma of contemporary Iraqi history is revealed here through personal stories that include death threats, militia killings, bombings and curfews.

Many of the women have divergent views about the war, or the democratic process, but they all patiently listen to each others' shared experiences of the Iran-Iraq war, sanctions, the current violence but also marriages (and divorces), grief, love and happiness.

"We returned to Fallujah. I wish we hadn't," recounts one woman. "The bombing and fighting had been so intense, people couldn't get out to bury their dead. So they buried them in their gardens ..."

"Every day you cross out a name in your address book," says another. "Someone's gone, died, been abducted, lost."

A third woman describes how much she hated a piece of furniture, a buffet, in her home. Ironically, it was "the one thing they [the Americans and the National Guard] didn't burn in our house ... If only they'd burned that!"

For Pachachi, the film addresses the process of shared expression. "In the Middle East, we are in desperate need of the courage to take on and speak about our experience honestly and we need to listen to each other without immediately judging. Perhaps this is a first step to regaining a sense of agency in our lives."

The mood is gloomy in Damascus the day Saddam Hussein is hanged. "We're supposed to be re-building the country on new democratic principles," one woman says. "... We shouldn't have a death penalty. I mean he was finished anyway, why not just let him die in jail? It's like beating a dead body with a shoe."

Pachachi gives the film just the right touch of relief from the intensely intimate and cloistered atmosphere. She shows the women walking around Damascus' streets practicing taking pictures. Everyone is happy to get involved, from the fruit vendors to street kids.

One day, the women travel to the Sayyida Zaynab Mosque south of Damascus, where many of the poorest among the estimated 1.5 million Iraqi refugees in Syria live. Here, they meet and photograph Sunnis and Shiis, some of whom were neighbors in Baghdad. At least in the mosque in Syria, they say, they can "hug each other, eat and talk together."

Dolberg begins to work with the women on subjects and storyboards for their photo essays. One theme that is discussed is fear and surveillance. "A door has become a source of anxiety for us now," says one woman, referring to incursions by American soldiers.

"Keep the camera on you all the time when you're home," advises Dolberg. "The more you shoot, the more you'll understand what you're doing ... but what's difficult is to get the right emotion."

The women's photo essays are affecting.

Um Mohammed, from Basra, has made a visual portrait of her city, with heart-breaking images of desolate parks and cityscapes, and felled palm trees. "It was the city of palm trees," she said. "It was full of them. Now, most of them are gone ... they were a symbol of Basra, the identity of the city."

Antoinette chooses "Motherhood" as her topic. She struggles daily to keep a sense of normalcy for her children. Her black and white portraits are tender and surprisingly professional.

"I started choosing my scenes, thinking about what they expressed ... I chose to show the particular way a mother touches her child. I would move the feelings inside me through the photograph."

Raya decides to photograph Baghdad's historic Mutanabbi Street after a powerful car bomb in 2007 destroys the street made famous for its bookshops and cafes.

"I remember how my feet walked this street. I used to think that my son too would grow up here. We stood among the ashes of the books and the ruins of the street ..."

Dolberg and Pachachi have done more than bring these Iraqi stories to a wider audience. By the end of the film, one is completely absorbed in the women's lives, anxiously waiting to hear more about them.

We learn that most have remained in Iraq and continue to take photographs. One woman, a journalist, has been assassinated. Another has died of cancer. Raya, who hoped she would find the strength to never leave Iraq, has immigrated to Sweden with her son after receiving death threats.

For more information the "Open Shutters Iraq" film and photographic essays see www.gulffilmfest.com and www.openshutters.org

Copyright 2009 The Daily Star

Audience comments for OUR FEELINGS TOOK THE PICTURES: OPEN SHUTTERS IRAQ

A brilliant shattering film.

This sense of weaving the lives of these women together with the wonderful "life maps"... the camera taking in their intimacy together, their comments on the slides, their photo trips out into the city, tears and sudden humour, but always this returning to their personal stories, you keep adding another few stitches to this garment weighted with grief and frustration. These women feel so full of intelligence and power, they simply seem to be seeking an affirmation of that latent power. I was so close to all of them, close even to their lives, their fears, their small triumphs. You have given us these voices, you have gotten them so far into us that we are forced to do something with them

Bravo for this wonderful film...We share the story of these women, their space, their joys, their food, their silence, much of their pain and grief, without once being voyeurs. You never make either us, the viewers, or the women feel ill at ease. It all succeeds and this is rare. I congratulate you for having found this difficult balance in each one of your shots. This is an essential film and it must be seen.

I was overcome by emotional and aesthetic charge. The pain, the participants' and the maker's, the subtlety and sensitivity of your lens, the beauty of the location and its generous people were so close to my heart. I thank you for such an enriching experience....

What a powerful, beautiful and extraordinary film. I was bowled over and very moved. A terrific achievement. It deserves very wide viewing I have been raving about it to friends.

Your film was an extraordinarily moving and powerful experience; I am still reeling from the intensity of it. It is a wonderfully reflective work, in every sense, psychological, social, political – and it has honesty and truth. I cannot remember when I was last so touched by anything I've seen on the screen. It should be required viewing for politicians, policy-makers and all who sit in high places in the world.

What an utterly beautiful film – rooted in the reality and courage of these inspirational women – struggling, in the face of insanity, brutality and war to find and connect with their own voice, to give value to their own experiences and shape them anew - and you ever-present, patient, listening, deeply humane. I believe this is the most truly feminist work I've ever seen.

You have a wonderful way of seeming invisible - as though you were handing the audience the camera and a map. You really make us feel as though we are actually there and exposed to everything without the comfort of artifice. You are taking us places and every turn is unexpected. The way you tell the story heightens our sense of alertness throughout the film. I do so hope this film gets seen more widely.

Your film is a remarkable, incredibly strong and confident piece of work. Managing the differing elements - the severity and pain of experiences recounted, as well as the humour the women use to present their life maps, and that you use through the juxtaposition of editing, or the way they discover the beauty in light falling in narrow backstreets – all this is a great achievement and I want to convey to you just how well that works

Open Shutters is magnificent and moving. It was incredible to hear the women's stories because we have become so dead to the news coverage of carnage and mayhem—knowing separated from feeling. We hope many people will see it. It is an oeuvre of conscience and witness. It was also beautifully shot and edited.

Reviews for RETURN TO THE LAND OF WONDERS

FRANCE

A remarkable and devastating piece of work showing an intimate Iraq as one has never seen it.

(3 stars) Hebdomidaire, France

With its unsettled rhythm, the film manages to translate the unreal atmosphere of the city. Traffic jams, barriers, electricity cuts, all journeys are difficult, and all activities slowed down. The torpor of a generalised waiting, interrupted by sudden floods of violence. An explosion, black smoke on the street, and above all the terrible testimonies. People talk about cluster bombs, the years of embargo, the lack of medicines, the persecutions and the torture of the old regime, those of the new regime, the looting and pillage of houses and of the riches of the country, nepotism and corruption, the rise of Islamism… Echoing this, the difficult compromises in drawing up the constitution take on a strong resonance. Maysoon Pachachi watches and questions. She lets herself be carried by the rhythm of the city and its inhabitants and reveals an everyday, intimate Iraq. The Iraqis seem resigned to let change happen, full of humour and kindness before the horror, in an improbable mixture of fatalism and hope.

Quentin Pinoteau, Télérama, France (Rating: TT (we liked it a lot)

BRITAIN

A personal and revealing take on the process of crafting a new country, with the director following her father, a very senior figure in the new Iraq, as he seeks to draft the country's new bill of rights. The recurring motif of city palms, viewed from the director's window in calm and storm, provides a lyrical barometer of the country's shifting fortunes, while Pachachi's unique footage of the horse-trading in negotiations, as well as her quietly observant study of the community of support and protection around a prominent public figure in an atmosphere of great violence, offers a compelling take on the risks and rewards of working on the cusp between the present tense and history.

Gareth Evans, Time Out, London

GERMANY

The director is in a clinic in Baghdad. She doesn't ask the standard question of a patient "What is wrong with you or how are you feeling?" She says "I hope you get better soon". If not before, then now you are ready to follow the film of Iraqi director Maysoon Pachachi wherever it takes you…

Maysoon Pachachi's image of Iraq is very different from the one we get on the western news – no US military, only an occasional helicopter in the sky, no assassinations, no pillars of smoke, no car skeletons, no zooming in on puddles of blood – but instead a walk through the copper and brass market, a visit to a hospital, a talk in a teachers' room of a famous and half destroyed secondary school. But still you never lose sight of war and occupation. They come back in the stories, which the director collects – from the present and from the time of Saddam Hussein's dictatorship. We hear about a hunger strike in Abu Ghraib prison, which ends fatally, long before the obscene photos were made public. One family is still looking for their son, missing since the war with Iran. A man sees a driver shot by US soldiers because his car backfires at a checkpoint…Poignant and revealing stories of an exhausted and tormented people…In this film, Iraq is given a face. We don't get a smooth or complete picture, but one that is complex.

Fritz Wolf, Suddeutsche Zeitung, Munich

This film is a careful, probing, journey, feeling its way through the dark both towards the future and into the past of Iraq and its people. We hear sentences like " who is burning our history?" or, after a short electricity cut "If only we could throw a switch, like this electricity, and start again from scratch". This is an episodic film that above all, talks about people who have lost almost everything in many wars and now after the most recent one in 2003, are once again trying to pull themselves together, re-building from scratch and this time without Saddam Hussein.

"Patience is the key to change", someone says and the Iraqis we see in the film are used confronting terrible trials of their patience in a despairing and yet, hopeful way. A woman has been waiting 14 years for her husband who fought in the Iran war, to come home. The father of a little girl, who has a serious face and a 101 Dalmations sweater, says "She needs insulin". A 17 year-old mother, who looks even younger, grins with a sort of urgent panic as she begs the director to send her some "good medicine" from abroad. Her baby has jaundice.

Always present – the palm trees and death, looking at first glance like contradictory leitmotifs weaving through the film. The palm trees are supposed to filter the terrible events and sights, but their subdued green is too weak to allay the horror or make it bearable. Or, maybe, the palm trees are too exotic, too strange to calm European eyes.

The stories are too shattering…In the last minutes of the film, we are jolted to Hyde Park in London and this brings us a measure of relief – joggers, deck chairs, lunch, trees with leaves, a sigh of relief and gratitude to have arrived in a place where questions of the future and the past are not so acutely felt. But the people of Iraq and their dead remain in our minds.

Florentine Fritzen, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, Frankfurt

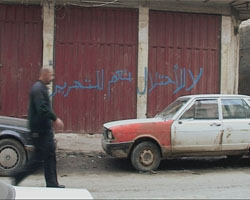

Danger sharpens the senses. One listens more carefully in Baghdad and one learns to differentiate between distant grenades and nearby bombs. For Maysoon Pachachi this is a new experience. The Iraqi woman director grew up in England and the USA and returned to her homeland in the spring of 2004. It was her first visit in 35 years. The filmmaker accompanies her father. The 80 year-old former foreign minister and ambassador was back after a long exile to try to help re-build the country. While Adnan Pachachi was discussing democracy with the experts and protected by 32 bodyguards, his daughter mixed with the people. ‘No to Occupation, Yes to Liberation" – graffiti on a wall. It sums up exactly the mood and opinion of most of the people of Baghdad.

No one is shedding tears for the Saddam Hussein, the dictator, but it insults Iraqis to be treated like second-class citizens by US soldiers.

Rainer Unruh, TV Today, Hamburg

USA

Returning to Iraq in February 2004 after a 35-year absence, Pachachi shows an almost sedate, dignified country attempting to rebuild in the face of an obstinate, largely unhelpful occupying force. Part tract on the perilous living standards of contemporary Iraq and part chronicle of the torturous slowness her father Adnan and others experience as they author the country's constitution, Return works best as a document of Pachachi's memory. As she revisits the formative people and places of her childhood, Pachachi achieves vérité lyricism, illuminating a host of lives shattered by both a ruthless dictator and the Western hegemony that replaced him—proving that the subdued, steady accumulation of facts and imagery is far more damning than any sound and fury.

James Crawford, THE VILLAGE VOICE, New York

Back in Iraq, a Stranger From the Outside World

Return to the Land of Wonders

2005 - UK - Special Interest

By JEANNETTE CATSOULIS, New York Times

Published: July 13, 2005

When the Iraqi-born filmmaker Maysoon Pachachi returned to her homeland in early 2004, it was her first visit in 35 years. Her 80-year-old father, Adnan, had become a member of the United States-appointed Iraqi Governing Council the previous summer, and Ms. Pachachi wanted to document the drafting of a transitional constitution and bill of rights. But in a country brutalized by wars, sanctions, and Saddam Hussein's cruelties, the creation of a unifying law seems as utopian as peace itself.

"Return to the Land of Wonders" is an on-the-fly diary of events and impressions that offers insight into the challenges of extracting democracy from chaos. As we follow the council's convoluted and frustrating attempts to merge sectarian interests with those of the United States, our understanding is framed by Ms. Pachachi's deeply personal narration. She worries that her father, who was Iraq's ambassador to the United Nations and foreign minister in the 1960's, is being "used" by the occupying forces, and her anxieties lend the film an engaging intimacy.

When the negotiations become wearisome, Ms. Pachachi takes to the streets, accosting her countrymen and women as they face the quotidian problems of occupation. At a teachers' workshop, an articulate group of women agitate against unpaid work and a state requirement that students be taught in the schools how to use guns. An old man explains how, during his many years in prison awaiting execution, he translated the novels of Steinbeck and others as a hedge against insanity. One young woman just wants to see the outside world. "Anywhere, it doesn't matter," she says sadly.

These random interviews, colorful and often impassioned, can be capsules of crime and survival. "Everyone's on the take," one man shrugs, confessing his involvement in gun- and sheep-smuggling, and citing the booming business in forged passports. As the looting and stealing facilitated by the invasion continue, distrust of the United States rumbles uneasily beneath an omnipresent hope for a better future. "Who are the Ali Babas?" another man demands. "Iraqis or Americans?"

For the patients at Baghdad's Medical City Complex, threatened almost daily by rockets and exploding mines, the question seems irrelevant. "Please, could you send us some good medicine?" begs a 17-year-old mother whose baby son suffers from jaundice, while a distressed father just wants finer needles for his diabetic daughter's insulin injections. Throughout, planes drone overhead and the electricity fails with dismaying regularity. "We have to think about turning over the black page of the past and starting again," an earnest young doctor says. On the evidence of this film, it won't be easy. NY TIMES

We've seen a lot of documentaries about post-invasion Iraq, but Maysoon Pachachi, the daughter of prominent Governing Council member Adnan Pachachi, delivers one of the most absorbing and ground-level views yet, thanks to her intimate perspective on the country's power elite. Showing how the political chaos behind the scenes mirrors the social chaos on the streets, Pachachi depicts the Iraq situation with a rarely seen degree of complexity.

NEW YORK METRO

Audience comments for RETURN TO THE LAND OF WONDERS

Quel voyage! c'était très émouvant, direct et pudique à la fois. On dirait que ça coule de source, mais ça n'a pas du etre simple ni facile.

(What a journey! It was very moving, direct and yet modest. It came straight from the heart, but it couldn't have been either simple or easy to make.)

Clair, émouvant, rythme intelligent, enfin on a pu voir et apprendre quelque chose sur l'Irak ! Mon amie Josie (et collègue) le regardait chez elle, elle m'a appelée à minuit pour me remercier de l'avoir avertie, elle ne tarissait pas d'éloge: "des vraies images, un vrai documentaire". Je sais comme c'est difficile ce genre de sport, bravo tu as réussit.

(Clear, moving, an intelligent rhythm and finally one was able to see and understand something about Iraq. My friend and fellow film-maker, Josie, watched the film at her house. She phoned me at midnight to thank me for having told her about it. She couldn't stop praising it: "real images, a true documentary"…I know how hard this kind of film is to make – bravo, you have succeeded.)

Enfin des gens qui parlent de leur pays, de leur vie, de leurs espoirs comme nous ne l'avions malheureusement jamais vu jusqu'à aujourd'hui. Quelle prouesse d'images dans cette horreur; ton papa et toi arrivent même à transmettre un peu d'espoir. Merci pour ce film, pour ton travail.

(Finally people speaking about their country, about their life, about their hopes as, unfortunately, we've never heard them doing, not till just now. What a strength of images in the midst of this horror; you and your father even manage to impart a little bit of hope. Thank you for this film and for your work.)

Remarkable film. My past experience in Sarajevo during the war made me recognize things, expressions, details, half-smiles and silences as true. Your father sitting alone, listening to a Bach violin sonata, that's an image that will stay with me for a long time with its density. And your old servant with his beautiful wife...Thank you.

The rhythm is very particular, lingering, taking pauses, straying from the main subject but always returning, all this made demands on my expectations of how cuts would work, how scenes would end but the style felt more and more pleasing and I stopped resisting or questioning it, just went with it…the wonderful smile of the young mother in hospital, the man who saved his sanity by translating novels and the vet who continues his interview even when the electricity conks. You have a great talent for catching these moments of aliveness of being able to wait for them to happen.

What an amazing film…a beautiful and intimate portrait…I think it is the first time I've seen a story on Iraq that is so close to the people and really filmed from within.

…a wonderful film, an excellent work. A quiet, sensitive and thought provoking revelation of the terrible issues facing Iraq but always keeping that in balance with the energy and determination of many people, especially women, to fight and create anew. (The) father, quite rightly, emerges as a hero in his steadfast insistence on the necessity for basic human rights. To me this is the main thing the last century eventually taught us. (The director) has a great way of giving people space and time in the interviews.

Reviews for IRANIAN JOURNEY

GERMANY

‘...the quiet, gentle rhythm of the picture has the viewer practically sitting between the passengers on the bus...the bus journey turns into a journey through the history of Iranian culture; the evocative and atmospheric images flow seamlessly into acute observations of everyday life...time and again, the director shows that it is impossible to make a film about women in Iran that is not a political...'

FRANKFURTER RUNDSCHAU

‘...a very informative documentary about a country in the process of upheaval and radical change...a highly successful synthesis of graphic, vivid detail and reflective commentary...'

STUTTGARTER ZEITUNG

‘Much more than just a portrait of an individual woman, this impressive and illuminating film gives a multi-levelled insight into Iranian society...'

AUGSBURGER ALLGEMEINE ZEITUNG

‘The director succeeds in giving an evocative, authentic insight into Iranian everyday life as it is hardly ever offered to us...Stunning, almost meditative shots - for example of the desert landscape and its inhabitants - along with interviews with other men, women and young people - intellectuals, manual workers and craftsmen - compliment perfectly the portrait of Massoumeh Baloghie, the bus driver...a brief, clear commentary examines and illuminates the political and cultural situation in Iran...A highlight in TV programming.'

MANNHEIMER MORGEN

‘Astonishingly frank interviews about emancipation and faith...these are complimented by beautiful, contemplative shots...'

BADISCHE NEUSTE NACHRICHTEN

‘...a high point standing out from the monotony and relentlessness of emotionally manipulative television...'

SWABISCHE ZEITUNG

FRANCE

‘Maysoon Pachachi's camera is attentive to gestures, plays of the light, the details of everyday life...Although the director follows the whole bus journey, the film is not properly speaking just a road-movie. The film escapes from the bus to search out the accounts of other women, artists, intellectuals - some well-known progressives, some of whom have paid for their beliefs by going to prison - but also farmers, traders, manual workers, shepherds, anonymous men and women who talk about their hopes, their frustrations and their economic and social situation. All these accounts mixed with those of Massoumeh (the bus driver), her husband, daughters and passengers on the bus, weave a portrait of Iranian society and the turmoil bubbling under its surface. A clear, illuminating documentary. A rich, informative enquiry into the status of women.

LE MONDE

‘...much more than a portrait of Massoumeh, the bus driver. In the process of the bus journey, Iranian society is revealed...'

LE PARISIEN

‘In a sense the film is a proper road-movie, things glimpsed fleetingly and subjectively, fragmentary portraits of people encountered on the road and through it all, the indomitable and gentle Massoumeh...the director treats everyone with consideration, not only Massoumeh, the pioneer, but also the unknown people she encounters at the roadstops and in Iran's provincial towns...(the long journey) allows the viewer to sense the truth hidden under the image of Iran presented to us so often as caricature...as the bus jolts along, we understand a bit about what it means to be Persian'

TELERAMA

‘A female sensibility, in its aesthetics both subtle and acute, looks at a changing society, a society of which we have not seen true images for many years.'

TELE 7 JOURS

‘Through the story of this character, the changing place of women in Iranian society is disclosed. A thrilling documentary.'

TELE LOISIRS

‘This documentary provides a stunningly shot picture of the country. A film not to be missed. (Unmissable).'

L'AMI DU PEUPLE

‘In the rearview mirror, a subtle portrait of Iranian society'.

VALEURS ACTUELLES

‘Maysoon Pachachi, in the course of her film, displays a profound humanity, treating with respect brave Massoumeh and equally all the anonymous people she meets on the road and in the towns and villages of Iran'

L'ECHO DE LA HAUTE-VIENNE

‘A poignant film, full of dust, prayers and hope'

TELETEMPS